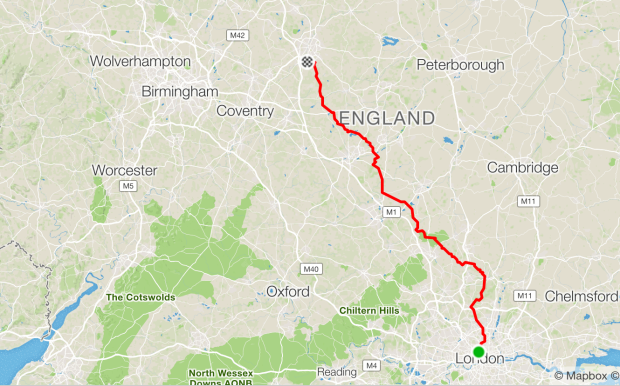

Day 1 – 114 miles

I headed to London on the 7.14am train to Euston with the commuters, but in my cycling kit, hair in plaits and nervous as for the day ahead. I did not know anyone and was going into the ride under-prepared and exhausted. We left UCLH at 8.45am winding our way out of central London, a peloton of white and yellow. London commuters greeted us with the opposite reaction to what I had expected. Drivers and pedestrians gave way to us, people called from the cars to ask what we were cycling for. No abuse, no honking, just space and encouragement. I loved London right then and felt a pride that we were, in our own small way, trying to do something positive for our community. I was for the first time cycling in the city feeling unafraid and, in the group, kinda invincible!

Leaving London – Photo credit to Al CG

This euphoric feeling did not last too long, by the time we reached the home-counties the drivers were rushing and impatient and a few near misses took place. I really struggled being on fast roads with cars overtaking closely. With little group riding experience I was consistently out the back and struggling to keep on the wheel in front. Eventually we were out into the countryside and things calmed down. Then I punctured!

On leaving the hospital I had missed my planned group so ended up in the group with the Royal Yeomanry army reservists. I am actually really pleased to cycle with these guys, they looked out for each other and were (well, up until the end of the ride…) always smiling and laughing. They also happened to have done a lot of cycling so were extremely competent at changing inner tubes! Within 30 seconds of my puncture the support van had pulled up, a fellow cyclist had my back wheel off and we even got a charity donation from the man whose front garden we were changing my tube in.

As the day wore on, the towns became smaller, cuter and more stereotypically British with little local pubs and bunting down the high streets. The roads rolled and so did we. The day was, however, pretty tough. From all my over-excitedness I had exhausted myself and the head wind was taking its toll. I chatted to everyone in the group, but when you are looking at the road it is hard to remember which story belonged to which cyclist. By the time we had passed 95 miles (the furthest I had ever cycled in a day) I nearly had everyone’s names. Our final stop before Leicester was at 100 miles. The support van greeted us with the good news that we had broken the £10,000 mark in our fundraising. On leaving the stop, I was exhausted and found mentally I just did not care anymore and let the wheel in front disappear into the distance. My knee was in a lot of pain and my brain turned off.

On route to Leicester barracks

We reached the Royal Yeomanry Barracks in Leicester around 12 hours after we left UCLH and were greeted by excited dogs, cheap beer, army trucks and really friendly army reservists who had kindly set up some ‘beds’ and cooked us our tea. The rest of the night was in the bar getting to know my cycle group better with quite a bit of banter.

Day 2 – 106 miles

I woke up after roughly 3 hours sleep, the canvas beds are ok, but I did not bring a pillow and I was too wired from the day to shut my mind off. The instant coffee at breakfast did nothing to dent the brain fog. Getting back on the bike was surprisingly fine and once out of Leicester I felt really great, far better than yesterday.

The day was gorgeous; hot, clear and windless. The roads perfect and views made me fall in love with England all over again. The first 30 miles flew by and the group were in high spirits. The hills grew as we travelled north- west in both steepness and in length. On the descents, down on my drops I was repeating mentally to myself ‘hold your nerve, Stace!’ to keep off my brakes as I hit speeds of 55+km/hr. With a lack of cars we played and raced each other down the hills.

‘Monkeys and Parrots’

Into the Peak district the day got even better, by far my favourite ever day on the bike, I was now falling in love with cycling! Being small the steep long hills are quite enjoyable – in the hard work this hurts kinda way that gets you addicted to sports! We had about four really great ascents and as you reached the top it looked like we were cycling along the lid of the country.

As we reached 200 miles into the ride spirits fell, and hard. Back into the towns amongst impatient drivers, and heading back into reality I went from not wanting the day to end to wishing it was over. Drained and exhausted the group fractured as some of the riders had totally blown up, and others were ready to dig deep for the final push into Manchester. It meant a lot of stop start waiting, and getting lost as Garmins ran out of battery and eventually tempers began to show. I had to laugh, you see it all the time when people get tired and emotions are near the surface at big events and the guys reminded me of my rowers at important regattas. We had cycled from London to Manchester – that is insane! The reality of the accomplishment sunk in and I took some gels to keep on the wheel. We free wheeled in towards the city. As we stopped and waited at each junction for the group to reform our group leader let his frustration get the better of him exclaiming ‘we should feel like cycling Gods!!‘

We eventually did make it, and as a group. It was over, we were here. Just to eat, drink, sleep and then head home in the morning to London, which only takes three hours by train.

OMG we reached Manchester!

It was an amazing couple of days and I gained a lot of confidence from achieving something I genuinely was not sure I could. Plus, it had felt a while since I got to laugh so much!

Thank you to everyone who sponsored us, we have raised over £13,000 and still hoping to get to £15,000. Thank you to Varian for our jerseys and to Max for helping me get back on the bike and train for this. Thank you to the Royal Yeomanry boys who took care of me (Matty, CG, Jenny, Rob and PMax) as well as the barracks for hosting us. And thank you to our support driver Stuart and biggest thanks to Steve for organising it all!

NHS Proton Therapy Background

The text below has been lifted from my thesis ‘Incorporating range uncertainty into proton therapy treatment planning’

Radiotherapy and Cancer

Cancer is a major worldwide health problem with approximately 11 million people being diagnosed with cancer and 7 million people dying from cancer each year (Dosanjh et al., 2008). Cancer Research UK (CRUK) reports that in the UK there were 331,487 cancer cases in 2011, 274,233 of which presented in England alone. Of these, 7490 cases were brain, other central nervous system (CNS) and intracranial tumours (Cancer Research UK, 2014c). Based on the same set of statistics, childhood cancers (<14 years) account for approximately 1% of cancer cases in the UK with 1,574 new cases of cancer diagnosed in children between 2009 and 2011. Brain, other CNS and intracranial tumours are the most common cause of childhood cancer death. (Cancer Research UK, 2014a).

Despite increased post-diagnosis life expectancy due to developments in early diagnosis and treatment, incidences of cancer will increase in the coming years due to the increas- ing lifespan of the general population. Of the adult patients diagnosed with a malignant tumour, CRUK estimates that 50% will survive their cancer for at least 10 years (Cancer Research UK, 2014b). For 40% of these patients, radiotherapy will play a role in their treat- ment, whether on its own or as part of a combined therapy. This corresponds to around 100,000 patients receiving radical radiotherapy each year in the UK; for 60% of patients it is given with curative intent.

External beam radiotherapy can include the use of high energy photons, electrons, protons or carbon ions. Proton therapy is considered to be advantageous in treating most childhood cancers and certain adult cancers, including those of the skull base, spine and head and neck. Protons, unlike X-rays, have a finite range highly dependent on the electron density of the material they are traversing, resulting in a steep dose gradient at the distal edge of the Bragg peak. These characteristics, together with advancements in computation and technology have led to the ability to plan and deliver treatments with greater conformality, sparing normal tissue and organs at risk.

NHS England

In 2007, the National Radiotherapy Advisory Group (NRAG) recommended for the De- partment of Health to give NHS patients access to proton therapy (Department of Health, 2014). A business case was proposed to establish English proton therapy centres and in the meantime overseas access was established. In the UK, patients have been able to access proton therapy abroad under the auspices of the National Health Service Proton Overseas Programme since 2008 (NHS Specialised Services, 2011). Between 2008 and 2012 160 patients, 107 of whom were children, were treated with proton therapy overseas. In 2009 NRAG determined that there was a need to treat up to 1,487 patients from England and the devolved administrations with proton therapy each year. Four hundred of these patients are classed as high priority patients, consisting of a casemix of complex cases including adults, children and very young children (Department of Health, 2014).

The decision to establish two proton therapy centres in the UK was made based on the costs, benefits and risks of each option investigated. Two centres, one in Manchester and one in London, has been determined to be the most cost effective option for the provision of the NHS service.

On the 10th February 2012, the Her Majesty’s Treasury and the Department of Health for- mally confirmed full approval of the Strategic Outline Case for the National Proton Beam Therapy Development Programme, pledging £250 million (Department of Health, 2014). It has decided that all patients treated in England with proton therapy, will be treated within clearly pre-defined protocols (Department of Health, 2014). With the aim to provide further evidence of the effectiveness of proton therapy every patient will also be enrolled into a prospective programme of evaluation with outcome tracking. It is hoped that the centres will start to treat patients in 2018 (Burnet et al., 2012; http://www.dh.gov.uk, 2012). There is no facility in the world that treats an equally complex casemix of patients as those proposed for England.

***

On the 22nd June 2017 Manchester received their cyclotron (the machine used to accelerate the protons to high enough energies to treat cancer) and London finished excavating the hole to house their centre.

We hope to hold another charity bike ride on the arrival date of the London cyclotron in 2018.

References

Burnet, N., E. Taylor, K. Kirkby, N. Thorp, R. Mackay, and M. G., Proton beam therapy for cancer: An important development for patients with an explicit agenda., BMJ, (344), 2488, 2012.

Cancer Research UK, CS_KF_CHILDHOOD, 2014a.

Cancer Research UK, Cancer statistics newsletter, 2014b.

Cancer Research UK, UK Cancer Incidence 2011 by country summary, 2014c.

Department of Health, National Proton Addendum, 2014.

Dosanjh, M., G. H. Corral, and L. M. M. Zentina, Development of Hadron Therapy for Cancer Treatment in Europe, AIP Conference Proceedings, pp. 12–16, doi:10.1063/1. 2979248, 2008.

NHS Specialised Services, NHS Specialised Services, 2011.